Jack of All Trades – Reign of the Super-Men

Reviews of SUPERBOY VOL.1: INCUBATION and SUPERMAN – ACTION COMICS VOL. 1: SUPERMAN AND THE MEN OF STEEL

The boys of steel take flight with the title that started it all, Action Comics, and the superhero that started it all, Superman. Along for the ride we have Superboy, Superman’s half-Kryptonian, half-human clone, created as a weapon for a clandestine organization bent on…well, something nefarious, surely.

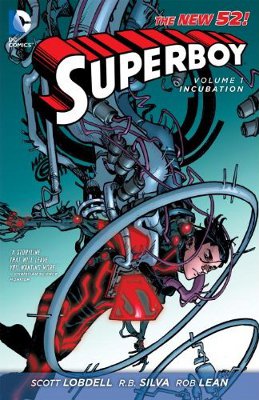

Superboy Vol. 1: Incubation

For every positive I can name about this book, there seems to be something to diminish it. The first trade release of three titles helmed by Scott Lobdell, along with Teen Titans and the much reviled Red Hood and the Outlaws. And both books share the same quality as Superboy, complementing each moments of exceptionalism with something to annoy the reader. With Teen Titans, it’s the atrocious art design and the underdeveloped characters, and with Red Hood and the Outlaws…well, we’ll get there eventually.

For every positive I can name about this book, there seems to be something to diminish it. The first trade release of three titles helmed by Scott Lobdell, along with Teen Titans and the much reviled Red Hood and the Outlaws. And both books share the same quality as Superboy, complementing each moments of exceptionalism with something to annoy the reader. With Teen Titans, it’s the atrocious art design and the underdeveloped characters, and with Red Hood and the Outlaws…well, we’ll get there eventually.

Best known for his work on various X-Men titles in the ‘90s and co-creating the teenage mutant team title Generation X, it’s no surprise that Scott Lobdell writes Superboy and Teen Titans like a bad ‘90s X-Men title with morally ambiguous characters who have to be goaded into heroism rather than take inspiration from their forebears and pursue of their own initiative. But, then again, maybe that’s what the Teen Titans needs. A radical shift from the norm and a break from the old formula. After all, isn’t that what the reboot is all about? Shaking up the status quo to entice new readers? (Well, of course not — it’s about sales but let’s humor DC for a moment.)

N.O.W.H.E.R.E., a secret, pseudo-military organization so enormous and all encompassing that not even senior staff know half its secrets — or even what the acronym stands for (which is in no way a cheap way of disguising that no one bothered to define the acronym disguised as a joke), with headquarters located, ironically enough, in the middle of downtown San Francisco…okay, no, it’s not, but that’s just as good as any of the “nowhere” jokes that actually crop up in the book. Here, a whole fleet of Dr. Insanos are hard at work engineering a Superman clone spliced with an unspecified human donor’s DNA (a secret which is either horribly telegraphed or building up to a disappointing red herring). Soon enough, Superboy makes his explosive debut, leveling the entire laboratory and killing dozens before N.O.W.H.E.R.E. subdues him and puts him to work.

Now, to be fair, Lobdell’s writing isn’t god awful. On the contrary, he pays more attention to constructing dialogue than an unfortunate number of writers currently working and the construction of this volume and Teen Titans leading up to The Culling crossover event shows that he pays a good deal more attention to plotting than those same writers. But at the same time, it’s immediately clear he’s one of DC’s lesser writers if for no better reason than that he isn’t a match for these characters, either as they were pre-reboot or, worse yet, as the writer tasked to reinvent them.

Now, to be fair, Lobdell’s writing isn’t god awful. On the contrary, he pays more attention to constructing dialogue than an unfortunate number of writers currently working and the construction of this volume and Teen Titans leading up to The Culling crossover event shows that he pays a good deal more attention to plotting than those same writers. But at the same time, it’s immediately clear he’s one of DC’s lesser writers if for no better reason than that he isn’t a match for these characters, either as they were pre-reboot or, worse yet, as the writer tasked to reinvent them.

To wit, Lobdell goes to great lengths to separate this Superboy from previous interpretations of the character, but this turns into another double-edged sword for the book. First, we have the revamping of Superboy’s suite of powers, extrapolated the implied telekinetic abilities of Superman, Supergirl, and other Kryptonian characters (e.g. the tactile telekinesis used to maintain the structural integrity of the large objects they lift, preventing buckling and structural collapse) into overt telekinesis. From an action standpoint, this works well, making Superboy more than just yet another brawler. It also complements his altered personality: where once Superboy was a moody, conflicted teenager prone to fits of berserker rage, this Superboy is very much reserved, emotionally muted and struggles to be more empathic and emotive despite his powers requiring undivided concentration and emotional stability. These changes are executed well enough on their own but in light of previous Superboy storylines, they ultimately add up to the same angsty moaning and groaning about being a clone, being a weapon, not fitting in, and all the same, tired tropes Superboy had already worn to death. So, regardless of all the aesthetic changes made to the character, he retains all the aspects of the character everyone grew tired of years ago.

Given the right material, Lobdell could probably write some exceptional DC superhero comics but that X-Men bug comes around to bite him in the ass. Here, he seems misplaced and I can’t help but pine for someone like Jeff Lemire to swoop in and show me something interesting. Nevertheless, to give Lobdell fair dues, despite much of Superboy’s character being conveyed through narration yet avoids the overwrought prose that comes with excessive narration, though the red text boxes clutter up a few panels. As well, the secondary characters — the female scientist simply known as “Red” for a majority of the book, Rose Wilson, and Superboy’s various handlers who come and go with circumstance — are all fairly well developed at least as far as necessary given the limits of their role. (I’d have liked to see more out of Rose Wilson, personally, but that’s just personal preference and not necessary to the book’s chosen arc.) Their interplay with Superboy and each other feels genuine and well crafted.

Given the right material, Lobdell could probably write some exceptional DC superhero comics but that X-Men bug comes around to bite him in the ass. Here, he seems misplaced and I can’t help but pine for someone like Jeff Lemire to swoop in and show me something interesting. Nevertheless, to give Lobdell fair dues, despite much of Superboy’s character being conveyed through narration yet avoids the overwrought prose that comes with excessive narration, though the red text boxes clutter up a few panels. As well, the secondary characters — the female scientist simply known as “Red” for a majority of the book, Rose Wilson, and Superboy’s various handlers who come and go with circumstance — are all fairly well developed at least as far as necessary given the limits of their role. (I’d have liked to see more out of Rose Wilson, personally, but that’s just personal preference and not necessary to the book’s chosen arc.) Their interplay with Superboy and each other feels genuine and well crafted.

The book tries to pose an interesting nature versus nurture argument as Superboy, free of N.O.W.H.E.R.E.’s influence, seeks out a place for himself in the human world and reluctantly comes to the rescue of diners being assaulted by a pair of metahuman criminals after committing several acts of incidental (and accidental) vandalism himself.  One gets the sense that Superboy must fight his instincts to heroism from his Kryptonian donor and instincts to narcissism (perhaps even villainy) from his human donor. But this motif isn’t well developed, at least in this book, pairing focus with Superboy’s confrontation with the Teen Titans and the Culling crossover event. So this subplot ultimately amounts to Suberboy moping some more and coming off as a bit of a twat, especially whenever he gets opines over his weaponized clone destiny.

One gets the sense that Superboy must fight his instincts to heroism from his Kryptonian donor and instincts to narcissism (perhaps even villainy) from his human donor. But this motif isn’t well developed, at least in this book, pairing focus with Superboy’s confrontation with the Teen Titans and the Culling crossover event. So this subplot ultimately amounts to Suberboy moping some more and coming off as a bit of a twat, especially whenever he gets opines over his weaponized clone destiny.

By no means is this book bad, it’s just not the type of book that will appeal to anyone with even a mild knowledge of Superboy and his typical suite of character traits and dramas. Even those who know him from only Young Justice will likely be put off by the radical changes to his personality. Regardless, even if you’re mildly interested in Teen Titans and the event arc Lobdell’s forging in that book, Superboy is necessary reading if only for the foreshadowing and insight into N.O.W.H.E.R.E.’s operations. If you don’t mind a radically different interpretation of an established character, then I can certainly say it’s worth at least a glance, but I don’t think, long term, you’re going to get an amazing Superboy story arc out of this writer or this setup.

Superman – Action Comics Vol. 1: Superman and the Men of Steel

Grant Morrison returns to Superman following an exceptional run on Batman prior to the DC reboot. Given Morrison’s All-Star Superman will make you love Superman regardless of how you felt beforehand, he seems the natural choice for this series of stories recounting Superman’s early days as Metropolis’s Man of Steel. All-Star effectively encapsulates everything amazing about the character — the altruism, the passion, the tireless struggle against evil, the conflict between man and super-man, the unrequited romance, everything — and his entire mythic legacy from Luthor to Doomsday in one twelve-issue mini-series, spanning the Golden, Silver, Bronze, and Modern Ages with nary a hiccup inbetween. With room to breathe here, Morrison draws a narrower focus onto a certain era of the hero’s history.

Grant Morrison returns to Superman following an exceptional run on Batman prior to the DC reboot. Given Morrison’s All-Star Superman will make you love Superman regardless of how you felt beforehand, he seems the natural choice for this series of stories recounting Superman’s early days as Metropolis’s Man of Steel. All-Star effectively encapsulates everything amazing about the character — the altruism, the passion, the tireless struggle against evil, the conflict between man and super-man, the unrequited romance, everything — and his entire mythic legacy from Luthor to Doomsday in one twelve-issue mini-series, spanning the Golden, Silver, Bronze, and Modern Ages with nary a hiccup inbetween. With room to breathe here, Morrison draws a narrower focus onto a certain era of the hero’s history.

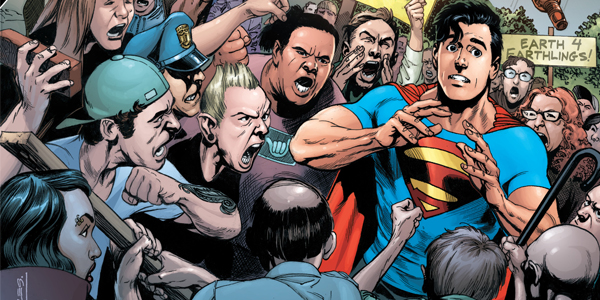

Here, Morrison returns Superman to his roots, specifically his Golden Age roots, roots many readers and writers had long forgotten — largely for the changing political landscapes the character has travailed for nearly a century now. A brief bit of history: Superman debuted in 1938, a politically charged time as the United States slowly emerged out of the dark days of the Depression and overseas the Second World War broke loose across Europe. The economy as it was, Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel conceived Superman as very much the New Deal superhero, a hero not merely for criminal justice but economic justice as well. Many of Superman’s early nemeses were not raygun wielding super scientists but corrupt businessmen abusing their workforces and bolstered inequality across the country. Making keen use of the historical parallels at work here, Morrison gives us a younger superman — more impetuous, more headstrong, more morally righteous, and very much informed by those early, socialist roots of Superman’s Golden Age origins — battling those old enemies at the fore of our economically depressed times: corrupt businessmen.

We begin with Superman assaulting a businessman, dangling him over the side of a fifty story building, demanding he confess to numerous crimes against the law and his workers — someone told Morrison he’s writing Superman again and not Batman, right? A good bit of Supes’ dialogue comes off a bit Batman-ish, as well. This is hardly the noble, high flying Superman we know, as embodied by his early costume of a T-Shirt, farmer jeans and mud-stained boots; similarly, Clark Kent is down on his luck as a reporter for a lesser known Metropolis periodical, assaulting Metropolis corruption in the press. While Superman’s flagrant act of assault goes fruitless, he nevertheless manages to save a group of people squatting in their former apartments (presumably victims of the housing crisis) from a wrecking ball bearing down on their homes but the government is having none of this rabble rousing heroism. Enter the U.S. Army and their special, anti-Superman consultant — one Lex Luthor — who, despite major difficulties, manage to subdue the Man of Steel, exposing him for the alien he is.

We begin with Superman assaulting a businessman, dangling him over the side of a fifty story building, demanding he confess to numerous crimes against the law and his workers — someone told Morrison he’s writing Superman again and not Batman, right? A good bit of Supes’ dialogue comes off a bit Batman-ish, as well. This is hardly the noble, high flying Superman we know, as embodied by his early costume of a T-Shirt, farmer jeans and mud-stained boots; similarly, Clark Kent is down on his luck as a reporter for a lesser known Metropolis periodical, assaulting Metropolis corruption in the press. While Superman’s flagrant act of assault goes fruitless, he nevertheless manages to save a group of people squatting in their former apartments (presumably victims of the housing crisis) from a wrecking ball bearing down on their homes but the government is having none of this rabble rousing heroism. Enter the U.S. Army and their special, anti-Superman consultant — one Lex Luthor — who, despite major difficulties, manage to subdue the Man of Steel, exposing him for the alien he is.

Morrison manages to cover a great deal of territory in the space of five issues and, honestly, the initial story arc here could have used the extra three issues to flesh out the story. As is, this is less Superman: Year One and more an extended flashback into Superman’s past before moving on to present adventures. We see how Superman transforms from proletarian firebrand into Metropolis’s resident champion for truth and justice but we also miss out on the Clark Kent aspect of Superman. Working at the Daily Star — the Daily Planet being a far-off dream — Clark’s interactions with Lois Lane and best pal Jimmy Olsen seem limited. You don’t really get why Jimmy and Clark are best friends when they never spend any time together outside their jobs while a majority of their dialogue is shared over the phone. Given how DC has pulled back on the Lois/Clark romance, Lois’s disinterest in Clark here seems natural and their confrontations have noticeably more spark to them.

During the course of events, Metropolis turns on Superman, damning him as an alien. Clark grows disheartened and retires the cape and shield, setting up the triumphant Return of Superman moment that, disagree if you will, never gets old — always puts a flutter in my heart, at least. But this moment is executed mostly in montage with Metropolis’s turn against Superman occupying scarcely a few panels with what could have consumed an entire issue. Worse, in moment of greatest weakness, Clark says “I failed you” to the spirits of Ma and Pa Kent, a scene that could have had immense emotional impact had it not been confined to one panel.

Nevertheless, it’s clear that this is much more a Superman book than it is a Clark Kent story; it’s about a hero growing into his own, becoming something more, so naturally interpersonal relationships take the sideline. Superman’s eventual battle for and championing of Metropolis rings true and I feel this take on early days Superman is universally heartening in that way only Superman can achieve. It’s classic comic book heroism at play as Clark transforms from the champion of the little guy into the champion of all people — rich, poor, big or small.

It seems hypocritical of me to punish Superboy for retreading familiar territory while Action Comics does plenty of that itself, but any amount of retreading or recycling of old material can be forgiven granted that the emotional core of the book shines through and connects, fostering sympathy with the character and their plight. This is where Superboy fails and Action Comics succeeds. Clark Kent doesn’t whine or mope or despair at his situation; her perseveres, conquers, and rises above regardless of the odds or the forces rallied against him.

Artwork by Rags Morales is some of the best produced by any of DC’s titles, especially during flashback sequences to Krypton and Superman’s amazing feats. And while Andy Kubert takes the reins after the first story arc, he produces some ominous imagery for Morrison’s Anti-Superman Army story arc. The book also contains several backup stories, wisely relegated here to the back of the book rather than interrupting the flow of the story (as per Detective Comics Vol. 1).

Artwork by Rags Morales is some of the best produced by any of DC’s titles, especially during flashback sequences to Krypton and Superman’s amazing feats. And while Andy Kubert takes the reins after the first story arc, he produces some ominous imagery for Morrison’s Anti-Superman Army story arc. The book also contains several backup stories, wisely relegated here to the back of the book rather than interrupting the flow of the story (as per Detective Comics Vol. 1).

All-in-all, you have a lot of what Morrison does best here: taking lavishly ludicrous and giving it a heart. While not reaching the heights of Scott Snyder’s Batman, this run of Action Comics is a must for any fan of the Krypton’s last son.