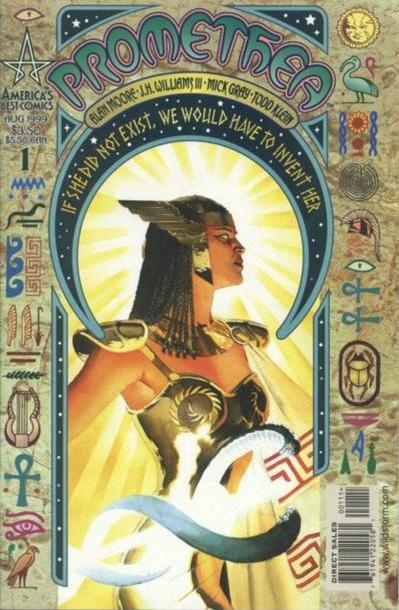

A Week Late #18: Promethea

A Week Late and a Few Dollar Short seems a bit of an understatement every time I post here. 16 articles in about 2 years, that’s unforgivable. No apologies. Never give up, never surrender, never accept blame when you can shoulder it onto the consequences of life.

A Week Late and a Few Dollar Short seems a bit of an understatement every time I post here. 16 articles in about 2 years, that’s unforgivable. No apologies. Never give up, never surrender, never accept blame when you can shoulder it onto the consequences of life.

I have recently finished reading Promethea by Alan Moore published from 1999-2005, 32 issues over 5 trade paperbacks and I’m slightly in love with the story in a way that I can’t remember being for quite some time.

Very appropriately timed to the writing of this article (clearly not timed with the posting of it) was the announcement that Neil Gaiman would be continuing the story of Sandman with J.H. Williams III on art duties. Sandman and Promethea are often compared as they both deal with the nature of the imagination, reality, unconscious creation, and the opposing powers of mankind’s desire to disbelieve and the necessity of his curiosity. Needless to say, I think, I am immensely excited for this project.

It’s been pretty rare in my (admittedly limited) experience with published human imagination that I come across a work of fiction that can change my perspective. It’s changed my perspective so much that I have been making increasingly grand and all-encompassing statements about how amazing it was. I experienced this same phenomenon when I first read the Screwtape Letters, or Phaedo. It happened when I watched Brazil or Dark City, and it happened when I read Gaiman’s Sandman, Morrison’s All-Star Superman and Arkham Asylum, Ellis’ Transmetropolitan, and so on. As highfalutin and grandiloquent as it sounds, I had a sort of realization of the immense amount of storytelling that I hadn’t allowed myself to realize was possible. All of these stories (though it is not a comprehensive list, to be sure) showed me a broadening of what could be done in that medium or what could be said about a character, time, place, or philosophy.

Maybe I’m selling this a bit high. Forgive me, It’s a damn fine comic book and I tend to get excited about that sort of thing.

WARNING: THIS REVIEW CONTAINS QUITE A FEW SPOILERS FOR THE SERIES PROMETHEA BY ALAN MOORE AND J.H. WILLIAMS III. IF YOU WISH TO READ THE STORY WITH SOME SURPRISES STILL INTACT, PLEASE DO SO, THEN COME BACK AND READ THIS.

The Story:

Promethea, at its surface and for a very short time, is the story of Sophie Bangs, a college student trying to figure life out and survive it while being the companion/avatar for a spiritual archetype of femininity and storytelling. The story takes place in the America’s Best Comics world of Alan Moore, and the last issue served as an effective ending of Moore’s universe (including Top 10, Tom Strong, Terra Obscura, etc.)

By the end of the first trade, the story is much less about Sophie and very much about the titular character and what she represents to the world. Promethea is a sort of protector to the world that we live in, a goddess of necessity, imagined by man for its own sake. Her role in the world, as is stated near the end of the series, is to bring about the apocalypse and in doing so, save mankind (backwards thinking, to be sure).

Sophie-as-Promethea journeys through the spiritual plane called the Immateria guided by the seven previous incarnations of the Promethea that were in our world (there can only be one avatar of the spirit at any one time) and a few other guests and discovers what her role in the greater scheme of the world is. The Immateria is presented as a physical or sometimes ethereal representation of collective human imagination, which in this story is what the entirety of what is known and what isn’t is built out of, humans being unique in their ability to imagine that which isn’t and make it real. Her path takes her across the many planes and levels of existence, through the Hebrew spheres of existence, across mythology and through the numbered paths of the Kabbalah. She encounters various entities existing as masters of archetypal ideas and still slaves to the collective human consciousness with themes lying heavily in freedom, power, and understanding of sexuality, the psychological concepts of Jung et. al., and the Magickal experiences of those like Crowley and John Dee.

Sophie-as-Promethea journeys through the spiritual plane called the Immateria guided by the seven previous incarnations of the Promethea that were in our world (there can only be one avatar of the spirit at any one time) and a few other guests and discovers what her role in the greater scheme of the world is. The Immateria is presented as a physical or sometimes ethereal representation of collective human imagination, which in this story is what the entirety of what is known and what isn’t is built out of, humans being unique in their ability to imagine that which isn’t and make it real. Her path takes her across the many planes and levels of existence, through the Hebrew spheres of existence, across mythology and through the numbered paths of the Kabbalah. She encounters various entities existing as masters of archetypal ideas and still slaves to the collective human consciousness with themes lying heavily in freedom, power, and understanding of sexuality, the psychological concepts of Jung et. al., and the Magickal experiences of those like Crowley and John Dee.

After issue 32, you realize that this was not an effort of the comic book medium to tell a story, but instead was Alan Moore’s pulpit. It was his soapbox and his stage from which to tell anyone willing to hear what he believes the universe is and the story was written to be a handbook to the madness. Throughout, the story is governed by his personal philosophies. There is an issue-long examination of the tarot, a meta-philosophy that combines bits and pieces of all religions, centered on the idea that a god is, by necessity and by imagination a result of that god’s conception by man, and a kabbalic road map for the higher planes of existence and imagination detailed in sight, smell, and experience and using Sophie-as-Promethea as our proxy.

There is, mind you, a running narrative in the real world, with Sophie’s best friend acting as a substitute Promethea for a time, a group of science heroes fighting to understand Promethea and stop various criminals, and the usual assortment of post-modern culture commentary that Moore intersperses within the background of panels and in “unnecessary” thought boxes on each page. The real world narrative ends as Promethea (*spoiler*) ends the world. However, this does not act as a literal end of the world. Humanity within the story receives an enlightenment and a union with the Immateria. The world continues, and people live on, but under a new mind.

The official end to the series was in issue 32, which when originally printed, was printed as a huge poster, with two 16-page sides acting as a symbolic art piece and an epilogue up the meaning behind the story. Promethea talks through the fourth wall to the reader, explaining what he/she just read and giving clarity and understanding to a shared spiritual journey.

It’s by no means perfectly written. At times, it is very clear that Alan Moore is enamored with his own worldview and wants you to join in the him-worship. At many points the reading is repetitive and daunting due to the mass of symbolism and Moore’s insistence on detailing the meaning of every experience, but the poetic (literally) effort of the tarot issue alone and the precision with which he crafted the narrative show his genius.

The Art:

The Art:

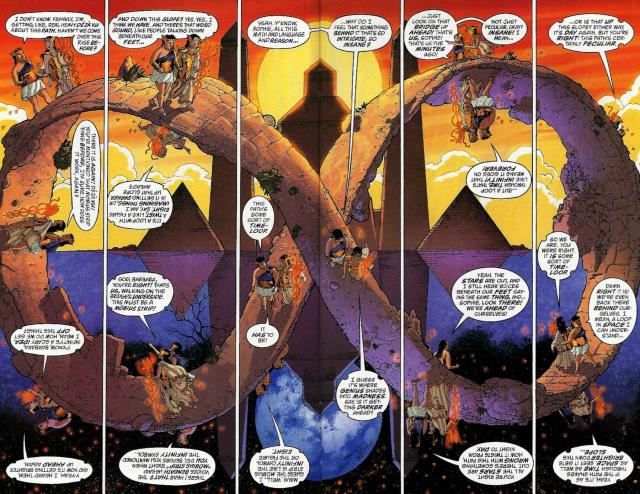

J.H. Williams III and Mick Grey wonders with every page. There is hardly an inch on any page that is not drawn with intent and with care. The real world pages are drawn fairly static and, probably very purposefully so to display the pages of the Immateria in comparative splendour. As with most Alan Moore efforts, the background is nearly as important to the narrative as the main action, providing commentary and enhancing/reflecting the themes. The layouts in particular are impressive, as the freedom and care that he adds meaning to each page is simply astounding. The art really shines, however, in the Immateria.

Williams, with differing visual styles, creates vastly different symbolic worlds for Sophie to travel through, from the blurry, unsure bottom of the imagination, through the fires of passion and rage, and the pure, uncontainable light of the “heaven” of the imagination. Each plane is unique, each world is tangible and accessible while maintaining the dense imagery and symbolism of the dialogue. Also of particular note are two issues, the tarot issue that I’ve mentioned ad nauseum which, while essentially simple is nearly perfect in its presentation of an isolated story, and the final issue which contains absolutely ridiculous amount of effort to make every page unique while showing 3 separate and cohesive narratives.

I only wish I was more qualified to comment on art, because this deserves a better judge.

• • • • • • • • • • •

Regardless of the content of the story and the merit of the writing of something so steeped in a personal philosophy, Promethea shows the pinnacle of what can be achieved in the graphic medium. To quote the book directly:

“Using language, we decode existence, make it lucid, cast light upon it. These marks on paper that you are reading are a program, running on the high-rez software of the human mind and it’s imagination. It’s also appropriate that I’m talking to you from the medium of a comic-strip story. Ideograms and Hieroglyphic picture stories were our earliest written language, how we recorded our exploits and our fabulous imaginings.”

Pentagon studies in the 1980s demonstrated that comic strip narrative is still the best way of conveying understandable and retainable information. Words being the currency of our verbal ‘left’ brain, and images that of our pre-verbal ‘right’ brain, perhaps comic strip reading prompts both halves to work in unison?

“We created fantasies then struggled to realize them. Everything around you right now originated in someone’s mind. Creating gods, goddesses, heroes and heroines, we tried to become like them, extending ourselves through sheer imagination.”

If gods are transcendent ideas, then the idea of a god IS a god. Divine images attempted to raise human consciousness using the power of art. Classical god-statues were intended for meditation purposes rather than worship, so that by understand a god’s qualities, we might reproduce them more fully in ourselves.

“Imagination can transform us. Yesod, the lunar sphere of imagination, is the foundation on which our spiritual life rests. Imagination arises out of consciousness, which itself blossoms from Hod, the mercurial, magical sphere of language.”

Promethea is a celebration of the imagination, filtered through the praise of language and graphical presentation and steeped in one man’s generous helping of crazy; one that all of you should read. Now, all I need to do is find the Absolute Editions for under $75.00.